Remember when banks couldn’t cross state lines? We do. Federal regulations prohibited the practice. Although, as the country stumbled its way through the Savings and Loan crisis in the 1980s, many states passed their own laws permitting out-of-state bank holding companies to acquire banks in their state under certain circumstances. By the time President Clinton signed the Riegle-Neal Interstate Banking and Branching Efficiency Act of 1994 into law, 46 states already permitted the practice.

But there was a problem. The Community Reinvestment Act, signed by President Carter 17 years earlier, was intended to “encourage” banks to help meet the credit needs of the communities in which they operate. With interstate branching now legalized, there was a concern that banks might gather deposits in the new state and then lend it where its original customer base came from. After all, they knew those customers.

Section 109 of the Riegle-Neal Act was drafted to assuage those concerns. Section 109 went into effect in October 1997 and was last modified in 2002. It says that, without imposing any additional regulatory burden or reporting requirements (i.e. using an educated guess), banks with covered interstate branches must pass a two-step test, which is generally conducted in conjunction with its Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) exam.

In order to pass the first step, a bank must show that its out of state branches have a loan-to-deposit ratio of at least half of the regulatory-published host-state ratio for those states, which is updated annually. If the bank passes step one, it does not have to go on to step two.

For example: Bank A is headquartered in New York but also has branches in Pennsylvania. Its loan to deposit ratio (LTD) for the Pennsylvania branches is measured and then compared to the Pennsylvania’s Host state ratio (currently 89.7% – page 7). Bank A’s Pennsylvania branches must have an LTD of at least half of that number. Whereas an LTD of 39% would have passed 5 years ago, today Bank A’s Pennsylvania branch LTD must be at least 44.9% in order to avoid the second step of the testing process.

Because banks only report branch deposits once a year (Summary of Deposits—June 30th data) and never report branch loans, the host state loan-to-deposit ratio is an estimate determined by total loans (from June 30th call report data each year) and total deposits from that state (from Summary of Deposits data) for all banks headquartered in that state.

For each bank headquartered in a specified state, regulators calculate the percentage of the bank’s total deposits that were determined to come from branches inside the home state and then apply that percentage to the bank’s total domestic loans.

If Bank A fails step one, or if there is not enough available data to make the determination, the bank moves on to step two: determining whether the bank is meeting credit needs. In step two, the examiner reviews the lending activity and CRA performance. It is “expected” that if the bank’s CRA rating is Satisfactory or better, it should receive a favorable determination under the credit-needs exam as well.

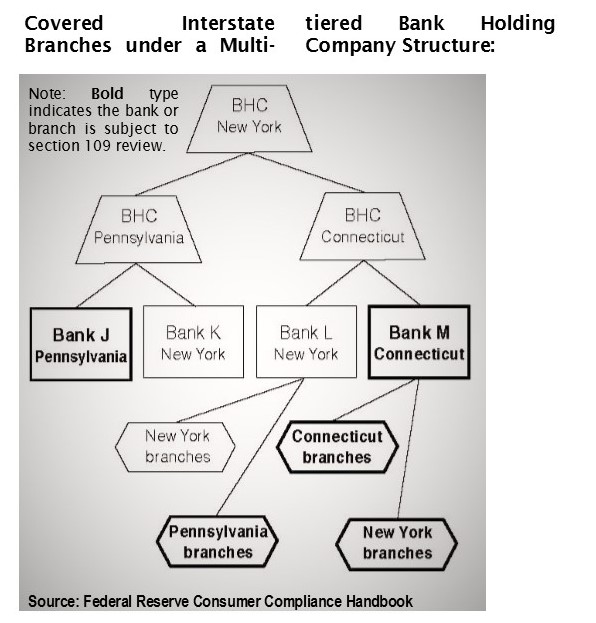

Where this gets really complicated is when there is a multi-tier holding company structure. The home state in this instance is where the top tier holding company is located. See diagram below.

Joseph Otting, Comptroller of the Currency since November 2017, has put a CRA rewrite high on his priority list. We’ll have more on this next week, along with a list of all U.S. banks that do not currently have a CRA rating of at least “Satisfactory”.