It’s been a year and a half since the hammer came down on Wells Fargo for opening millions of new customer accounts without their consent or knowledge. Employees went so far as to transfer money between fake accounts to build overdraft and insufficient fund fees. As a result, more than 5,000 employees lost their jobs and the CEO (John Stumpf) was forced to step down. But at just $185 million, the financial penalty amounted to a slap on the wrist to this mega bank (JRN 33:40).

It turned out that was just the start of Wells Fargo’s woes. Before she left her post as chairman of the Federal Reserve, Janet Yellen lowered the boom further by imposing a growth cap on Wells Fargo. “Until it ‘sufficiently improves its governance and controls,’ Wells Fargo is not allowed to grow beyond its year-end 2017 size of $1.95 trillion in assets” (JRN 35:07).

Now (Friday April 20th to be exact), Wells Fargo consented to pay $1 billion jointly to the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) and the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB), but not for fake accounts. This was for an altogether different scandalous act.

This time it was mortgage borrowers getting the short end of the stick. If a mortgage doesn’t close during the initial interest rate lock period, it is generally the responsibility of whomever was at fault for the delay to pay the rate lock extension fee. However, from at least September 2013 and through March 2017, Wells Fargo was charging mortgage customers interest rate lock extension fees even when it was the bank’s own fault that the mortgage did not close on schedule.

What an easy way to make money. If that were legal, every mortgage lender would be delaying closings and racking up the fees …but it’s not. Nor is it legal to force auto loan borrowers to purchase insurance—policies underwritten by their own third-party vendor. But they did. The added cost stressed some borrowers credit ratings while others lost their vehicles altogether.

Stumpf’s replacement, Tim Sloan says the bank is “making progress”. It better speed it up. Two of its units are still under investigation.

You will rarely, if ever, find this kind of abuse in a community bank. While community banks are just as likely to try to cross-sell customers on additional products, they do not have the high-pressure sales tactics and mandatory quotas that some of the big banks have. They are actually on your team, trying to do what is best for you and the bank and the community as a whole.

Aside from the that, it’s hard to defraud someone you might run into at the PTA meeting or the grocery store. In fact, page 7 lists the U.S. banks with the highest dollar volume of service fee income in 2017 …not one is a community bank!

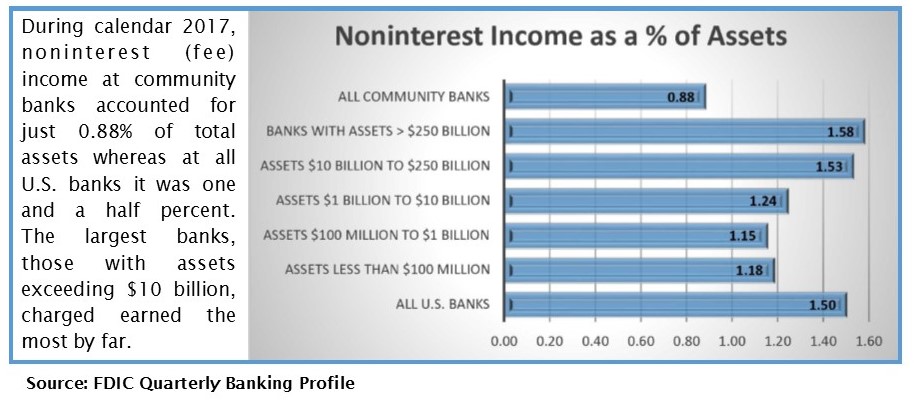

To be clear, we are only referring to service charges on deposit accounts in domestic offices. Page 7 does not include other noninterest income; the chart below includes all noninterest income (NII). You see that NII at banks with more than $10 billion in assets averaged more than 1.5% in 2017. Community banks averaged just 0.88% last year. Since NII includes product lines that most community banks don’t carry (like wealth management) it isn’t really an apples to apples comparison. Comparing just that one line item “Service charges on deposit accounts in domestic offices” as a percent of total deposits,” community banks averaged 0.20% in 2017, non community banks averaged 0.28%.